December 5, 2019 to December 8, 2019

11 am to 7 pm

(open until 8 pm on December 6 and 7)

IAMAS Gallery 1, 2 & Reception Room, Hall A (Softopia Japan 2F, 3F, 4F)

Admission Free, no reservation required

Where do new creations come from? As society becomes increasingly informatized, its creation and distribution processes are transformed. As the individual is informatized and multi-level networks develop, the power to recombine these things is required.

The Gifu Ogaki Bienalle 2019 is inspired by these issues, focusing on the environment in which architecture, design and art are produced as a public sphere. What do we mean by public sphere? A space that anyone can access, predicated upon difference and human interaction, located in the gap that exists between different values and opinions. We focus on the production environment in order to investigate how media technology might change the relationship between creator and user, audience.

Specifically, we will consider the current state of the production environment, focusing on proposals for cooperative design spaces by users, engineers, and designers, and on showing a new model for applying the next creation and archiving creative activity of artists created together with machines. Through the symposium and related works exhibition, we are planning a public sphere to critically capture media creation.

The internet came into widespread use in the mid 1990’s. Smartphones took off in the latter half of the 2000’s. Networks, formerly called virtual space, became more and more a part of reality. The Arab Spring, which began with the 2010 Tunisia/Jasmine revolution and the 2011 Egyptian revolution, was a powerful example of the driving force that Social Media can exert. Similarly, the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 showed the fallibility of existing infrastructure and became an important reminder for how to rebuild community. As these events demonstrate, networks have permeated our everyday lives.

What kind of knowledge can we build in a society based on such a system created by others? In this biennale, through a four-day symposium, we reexamined the design movement that was trying to find a new interface between society and technology from a historical perspective, and the ephemeral and performative values that media technology brought to modern society. At the same time, we will discuss the public/intimate sphere from the standpoint of actual production, design born from collaboration, and proposals for how to interact with others called AI.

In recent years, the popularization of digital fabrication machines has opened up new possibilities for individuals who want to make things. On the other hand, however, few have tried to address how these machines can be used alongside conventional technologies and how they can serve to critically investigate design by revealing the design process. We seek to address these issues, beginning not by looking at technological theory, but by researching how these machines were actually used by small and mid-sized firms. Creators combine these machines with conventional technology and use them in a myriad of ways. Our project methodology affirms these differences and encourages varied creators to cooperate, discover and develop never-before-seen possibilities. All of this takes place within a cooperative design environment. In this exhibition, we display prototypes born out of from cooperation in the process for establishing a cooperative environment.

Archiving is the activity of recording, storing, and conveying creative acts. It leads to new creation; therefore, it is an essential platform for human creativity. Traditionally, we have utilized media such as text - humans-written characters - as well as still images, movies, and recordings - machine-written characters - as a means of archiving. However, these forms of media have limitations: they can only deal with what people can verbalize and preserve only what people decide to record. Our project focused on artificial intelligence as a new medium for recording the creative acts of an author (including unconscious ones) during the production process. Artificial intelligence is often contrasted with humans and is often seen as a dangerous entity that takes away people's jobs. However, there are possibilities that we humans can develop only through co-creation with artificial intelligence. For example, by facing off against artificial intelligence, young shogi players are developing and opening up new phases of the shogi culture that people have fermented over a long period of time. We are exploring new forms of artificial intelligence where it is neither a mere tool nor the slave of humans. At this exhibition, we will exhibit some of the results of our research as media artwork and propose the concept “Archival Archetyping.”

Koki Akiyoshi / Hideki Ando / Kenji Horie / Kyo Akabane / Yasuko Imura

Focusing on how the use of digital technology in fields like architecture, wood working, and printing is changing the relationship between designer, creator, and user.

Nao Tokui [online participation] / Shigeru Kobayashi / Ryota Kuwakubo / Shigeru Matsui

How do artists conceive of AI as an environment for artistic creation? What possibilities does it hold? The artworks in this exhibition will jumpstart that discussion.

Haruhiko Fujita / Takashi Kurata / Yasuko Imura

Reinterpreting the perspectives of the Arts and Crafts Movement and Mingei , the Japanese folk craft movement, we will consider the current form of the relationship between designers and users.

Mariko Murata / Shoko Tateishi / Takeshi Kadobayashi / Yasuko Imura

We will discuss the possibilities of performative/ephemeral art works by looking at changes in the public/intimate sphere brought about by our modern media environment.

Digital fabrication machines have become more and more prevalent, expanding the ability of individuals to make things on their own. However, this has not resulted in Digital Fabrication’s rarely used alongside conventional industrial technology or in an improvement in the design process itself. With the help of Fuji Kogei, inc. and Horie Orimono, inc. we reexamined the design process itself from a meta-perspective incorporating production and organizational theory, looking at new possibilities for digital fabrication.

Photo: Ryuichi Maruo

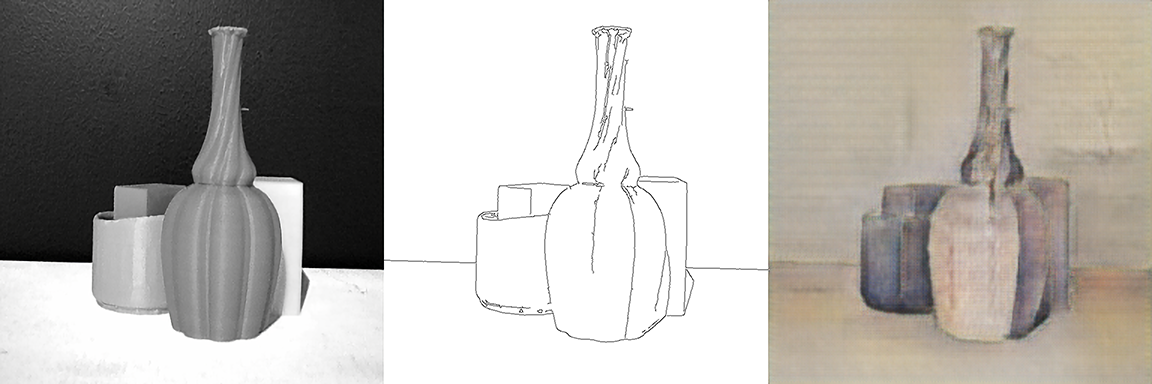

Giorgio Morandi painted still-lifes based on the spatial structure of things. His intention was to distort figure and ground. With “AI” that has learned to study the marks of his creative activity serving as an “eye,” we will exhibit The Room of Morandi – an experiential piece in which viewers restructure the world of the artwork with their own hands – along with two other pieces. Qosmo – a team that specializes in the research and development of algorithmic creation – has been invited to exhibit two of their works: the experiential piece Neural Beatbox and the development environment Qosmo AI Music Tools Tools.

«The Morandi’s Room»

Direction: Ryota Kuwakubo

Development: Shigeru Kobayashi

Text: Shigeru Matsui

3D modeling: Yoshiyuki Otani

Research: Xinqi Zhang

«Neural Beatbox»

Concept / Direction: Nao Tokui (Qosmo, Inc.)

Research / Management: Max Frenzel (Qosmo, Inc.)

Development: Robin Jungers (Qosmo, Inc.)

Design: Alvaro Arregui (Nuevo.Studio)

ABSTRACT

Rhythm is one of the most ancient means of communication. Neural Beatbox enables anyone to collectively create beats and rhythms using their own sounds. The AI segments and classifies sounds into drum categories and continuously generates new rhythms. By combining the contributions of viewers, it creates an evolving musical dialogue between people. The AI’s slight imperfections enrich the creative expression by generating unique musical experiences.

BACKGROUND

Through interactive design principles, this audiovisual installation allows for collaboration between a user and the AI system; while the AI guides the creative process and makes decisions, the content itself only comes from humans. This resonates with the practice of beatboxing, where the instruments are removed from the equation to put the emphasis on the creative potential of the individual. Here, the AI becomes a tool and enabler for natural expression, trying to make the best out of any human-produced content. Despite the computational process involved, it remains imperfect and produces results that might meet expectations or not, adding a creative element of surprise and novelty.

TECHNOLOGY

One critical aspect of the installation was to propose a setup intuitive enough to allow for a fully interactive experience, while still showcasing the potential of machine learning in the context of music production. In order to do so, the system was designed from server to client-side; The AI system is divided into two parts:

1. CLASSIFICATION OF SOUND

The first step is to receive sound files (recorded from users), divide them into meaningful segments, and use a neural network classifier to classify them into one of eight possible drum categories (e.g. “kick”, “snare”, “clap”, etc).

2. GENERATION OF RHYTHM SEQUENCES

The second step is to generate beats — sequences of drum patterns — that will be played. This generative part is also the result of a trained neural network - a VariationalAutoencoder (VAE) - but it involves extra processes that give us more control over the choice of sequence: for instance, each drum can be weighted in order to pull a beat with more relevant items within the current context (e.g. if a user records a kick, we will want to update the beat with a sequence containing a kick).

The client-side runs as a web app, and makes uses of the moderns features provided by browsers: media recording API, advanced graphics, etc.

This allows the application to be accessible from any modern machine with minimal configuration.

In the context of the event at the Barbican Centre, the system behind Neural Beatbox was first designed to run as an exhibition app, and thus features reduced interactions to fit the simple interface provided on-site; In the long term though, it is planned to evolve into a proper browser-friendly application, to allow anyone to access it from a browser and experiment with it.

While the data processing could be done in the browser with modern APIs, delegating the heavier computations to the server lets us have more control over the smoothness of the process. Being centralized, it also opens doors for further iterations in the future; collaboration could now potentially happen across users, establishing a connection between them, with the AI acting as a "curator" in the middle.

DESIGN

In order to convey the intents of the experience and interaction with it intuitive, the visual setup had to go through a proper design process. We collaborated with Alvaro Arregui (Nuevo.Studio) for that purpose, and developed a set of animations to reflect the dynamics of the music, and give a rhythm to the piece, visually as well as audibly.

«Qosmo AI Music Tools»

Concept / Direction / Development: Nao Tokui(Qosmo, Inc.)

Research / Management: Max Frenzel(Qosmo, Inc.)

How does the music production process in the future look like? Is it possible for us to use AI to create new kind of music? We, as Qosmo, have been working on AI tools allowing artists to explore their novel ideas with the help of AI. Since any AI systems are based on it can be a limitation for artists to use AI model developed/trained by someone else. So we prioritize the ability for artists to use/customize freely according to their needs.

As the first publication of our series of AI Music Tools, we have developed and released two systems/softwares.

1. M4L.RhythmVAE/M4L.MelodyVAE for Ableton Live/Max for Live

Variational Autoencoder(VAE)-based rhythm generation device for Ableton Live/Max for Live. This plug-in software allows artists/musicians to train and use the rhythm generation model within the music production software(DAW).

Users of the device can drag and drop MIDI files containing rhythm track and train the model. Once trained, they can automate the transition of the latent vector of the VAE model and generate dynamically changing various rhythm patterns.

The device simplifies the otherwise complicated and cumbersome process of training and utilizing generational models and allows artists to explore the possibility of AI freely.

2. SampleVAE - A multi-purpose tool for sound design and music production

Deep learning-based tool that allows for various types of new sample generation, as well as sound classification, and searching for similar samples in an existing sample library. The deep learning part is implemented in TensorFlow and consists mainly of a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with Inverse Autoregressive Flows (IAF) and an optional classifier network on top of the VAE's encoder's hidden state.

We aimed to democratize the use of AI in the music production process.

Qosmo / Established in 2009, Qosmo uses algorithms in the process of creation to reveal new forms of expression. The name “Qosmo”, derived from “cosmos”, holds meaning in two extremes, “the order of the universe” and an “ornamental flower”. Their recent work incorporates artificial intelligence and algorithmic design with the motto “Computational Creativity and Beyond”.

Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences [IAMAS], Ogaki City

Yasuko Imura

Kyo Akabane, Yasuko Imura, Shigeru Kobayashi

Hiroki Tomita

Jincho Iguchi

Action Design Research Project

Archival Archetyping Project

4-1-7 Kagano, Ogaki-shi, Gifu 503-0006 JAPAN

TEL : +81-584-75-6600

E-mail: event@ml.iamas.ac.jp

Web: /

Flyer: PDF

Handout: PDF

© 2019 IAMAS